Jacqueline Gellens Watson’s Life With OCD

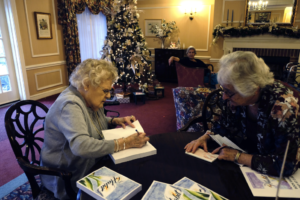

The following is an excerpt from the new book The Habit, by Jacqueline Gellens Watson.

In the 1930s and 1940s, mental illness was not widely accepted as a reality in America. When I was a child, I developed a mental condition, later called obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), due to prior circumstances in my life. I couldn’t understand what I was going through. I first noticed it when I was reading the book, Lorna Doone. I couldn’t understand some of the passages. I would fixate on them and go over and over them in my mind, trying to understand the meaning of the words.

I worried about everything. These worries are called “symptoms” of OCD, I later learned. As I began to realize that something had gone wrong in my mind, I began to sort out systems whereby I could handle the worries and feel safe. But it had to be secretive; I didn’t want anyone to think I was crazy.

So, I began to put the worries in a file folder, so to speak, but what to do with the files—each of them containing an unresolved worry? I was only 10 years old, but I had seen file drawers. I decided my arm would be the “file drawer” where I could place the worry files. Then I devised a system where I would blow on my arm at the end of the day, thus eliminating the files with the worries in them. That’s how I managed these unwelcome thoughts for a while.

But then my parents noticed my peculiar behavior and admonished me for developing such a crude habit. Naturally, I couldn’t tell them what I was doing. They wouldn’t have understood, and I didn’t know how to put it into words. I also didn’t want them to think I had completely lost my mind. Actually, at the time, I didn’t think I had lost my mind—I thought I had just developed a bad habit. I would say my prayers each night and ask God to “help me break my habit.” Thus, the title of this book. It was important not to let anyone know of my affliction, so I kept the disorder in my mind rather than displaying overt symptoms like washing my hands incessantly or not stepping on a crack in the sidewalk. My obsessions were (and still are) private. The condition made me seem slow to some people. I couldn’t follow directions quickly. I couldn’t hit a softball, and after two tries at playing golf, I just forgot about it. I couldn’t even hit the golf ball. But I was good in school. I usually finished close to the top of the class.

But there were other problems in which this disorder would manifest with me. Once, I watched a movie about a serial killer, and for two days wondered if I had killed someone! Other instances made me feel like I was going mad, too. I went to a few different doctors and was put on various medications, but I had to keep going back because, at times, the habit to obsess was too strong for the pills. It felt like I had to do a specific thing (whatever my brain dreamed up) to make my world safe. Living with my family who did not have the same mental health challenges as me, meant not only did I not understand why I had a sudden and irresistible urge to understand a senseless passage or saying, but they had no idea why I acted the way I did either.

As I write this, there have been huge leaps in medical advancements and treating OCD. But when the symptoms first appeared, people didn’t trust psychiatrists. Later, when I first consulted a psychiatrist, my husband at the time was suspicious of the supposed care the doctor wanted to give me. People made the comparison that if they weren’t sick, if they were able to control their bodies and their minds, then there should be no reason why I couldn’t do the same. But I couldn’t. When I convinced myself I had been assaulted, or that all the teachers believed I was cheating, the thoughts just looped in my mind. I couldn’t listen to reason, and I was far too embarrassed to tell anyone what I was struggling with because I knew they were different from me. It was exhausting to fight so much at times, to have no control over what I HAD to do to work through an emotion or upsetting event. I had to follow the orders my brain was giving me . . . even if my brain was broken.

I now know that OCD means people repeat actions because it makes them feel safe. It gives them a sense of control, even when what they are is mostly out of control. One in about 40 adults are diagnosed with OCD in America each year, but back when I was young, I felt like I was the only one who had “thought trouble.” That’s why I want to share my story. I want to give people who are suffering with it hope. I want to tell you that you don’t need to feel ashamed for requiring medication. You don’t need to perceive yourself as broken. Can you imagine what it would be like to go through life unable to resist your urges, and mostly worrying about everything? I can. Wherever I was, I had to listen to what my brain was ordering me to do, even if it was in front of strangers and family and schoolmates, but of course, I did what I could to control myself.

When I couldn’t control myself, this resulted in mortifying situations, which I share here with you. Many times, it meant that I became even more withdrawn because I knew something was wrong and I desperately wanted to hide as I was forced just to carry on and go through life. Goodness knows, I constantly tried to make up rules around my OCD. I thought if I resigned myself to handle the compulsions by these rules that I was managing my obsessive compulsions. But I wasn’t.

I hope you will enjoy this story of my life, which in addition to explaining my disorder, relates the reality of the Depression era. Take a trip with me to an earlier time when gasoline was so expensive sometimes a family had to sell their car, and when the dynamics between men and women dating were vastly different. Let me tell you about my upbringing with a combined family, and how when I discovered I was pregnant was married in one week! My life does not resemble the stories that you hear and read about from this time period when women were reserved and dated very few men (and sometimes only one) before settling down. My adventures kept pace even with the women of today. But as I lived them, I was an outcast because while others were on track to a sensible existence, I wasn’t.

My life changed many, many times, and all the way through I just tried to do the best I could. Now, I am in my 90s, and my mind is sharp, my memories as vivid as if they occurred yesterday. Yes, inventions come along, laws change, and society progresses. But regardless of the time in which you grew up, people are the same. They want the same—love, acceptance, and confirmation that they are as normal as anyone else. And it doesn’t matter who’s in the White House, what war is waging, or where we are in the battle of the sexes. Despite the historical references that I have included in this book, I think there will be times when you are reading that you will forget about the years that have flown by from then to now. Because we are all the same at our base.

If you are reading this and fighting your own habit, the best advice I can give you as one who has survived with and without medication is to get help. You need to tell yourself it’s okay that you have this condition. We know more about people living with OCD than ever before, and it is so much easier to get through your days when you have a treatment plan. You don’t have to feel alone, like an oddball, or as if no one understands, because OCD is real, and people today know it is a genuine affliction. Since I was a young girl I have lived with this disease. If I can do it, you can, too. Don’t do it the way I did, though. Don’t deny yourself the care you need to be happy.

It looks like America is on the way to outgrowing the shame of mental illness. It’s about time.

Learn more about The Habit by Jacqueline Gellens Watson,

check out the book site: https://epicauthor.com/thehabit2

Available for Media Interviews: